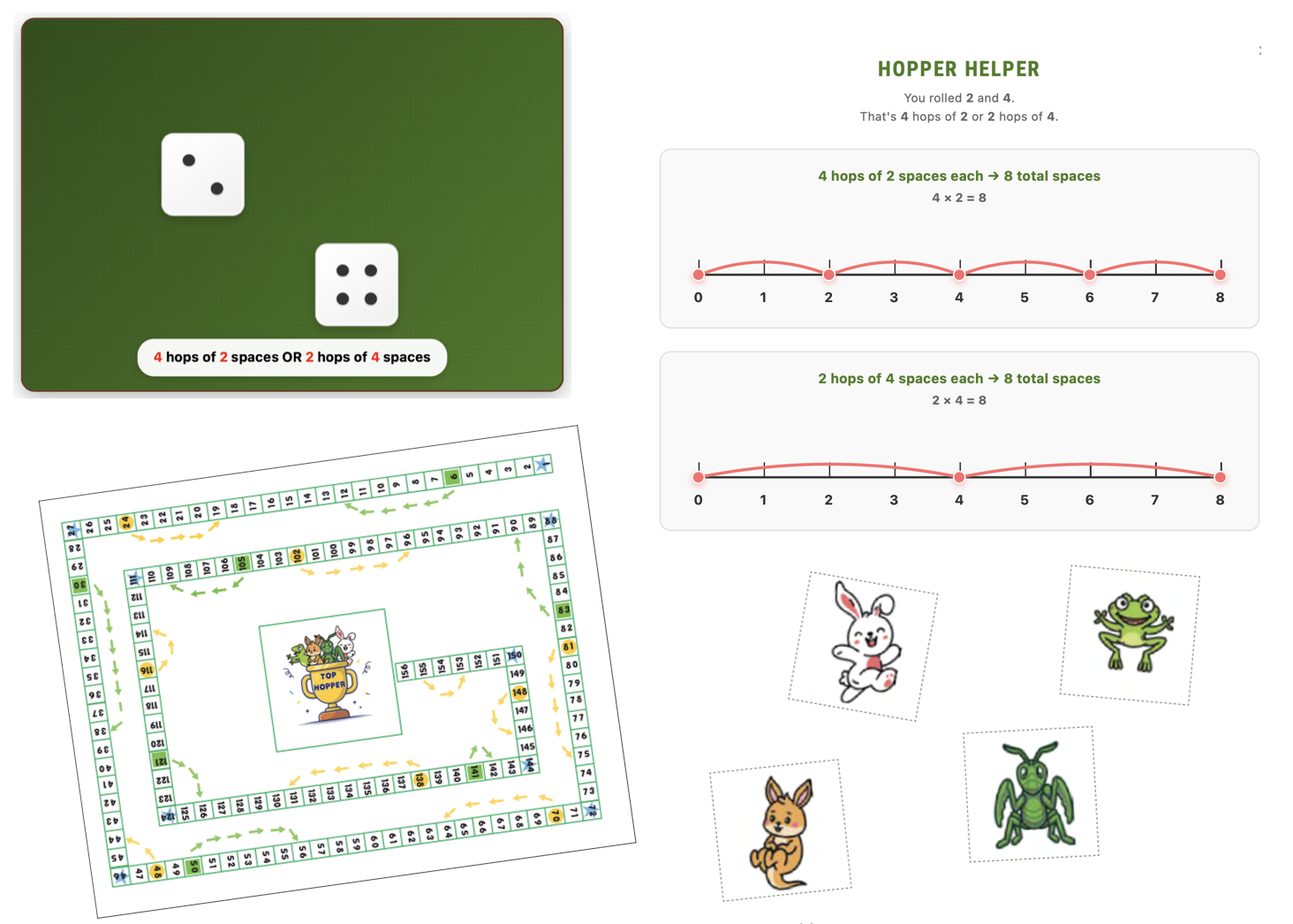

Each dice roll requires students to interpret two numbers as equal groups. When rolling 4 and 6, students choose whether to read this as "4 hops of 6 squares" or "6 hops of 4 squares"—both yielding 24 total squares, but requiring explicit recognition that multiplication can be read in either direction. This interpretive choice grounds multiplication in physical movement rather than abstract calculation.

The core mechanic develops translation between three representations: the dice showing two numbers, the verbal statement "X hops of Y squares," and the total distance moved. This translation process builds understanding that multiplication describes situations where equal groups are combined. A roll of 3 and 5 doesn't just mean "15"—it means three groups of five things, or five groups of three things.

The language structure "X hops of Y squares" provides consistent linguistic scaffolding for the equal groups meaning of multiplication

The word "of" signals multiplication in mathematical language. When students say "2 hops of 5 squares," they're describing a specific action: hop once to move 5 squares, then hop again to move another 5 squares. This verbal structure connects naturally to written notation: 2 groups of 5 becomes 2 × 5. Consistent use of this phrasing across all turns reinforces the linguistic-mathematical connection.

The Hopper Helper visualization represents multiplication as iterated groups along a number line. When students see their 2 hops of 5 displayed as two jumps from 0 to 5 to 10, they observe multiplication as repeated addition with visual support. The number line representation connects discrete groups (2 hops) to continuous quantity (10 squares total), bridging counting and measurement interpretations of multiplication.

Strategic thinking integrates calculation with spatial reasoning: Landing on green squares provides bonus forward movement, yellow circles force backward hops, and blue stars swap positions with opponents. Students calculate not just their product, but also where that result will land them and whether special squares affect their trajectory.

The commutativity of multiplication becomes practically relevant through player choice. A roll of 2 and 6 can be interpreted as either 2 × 6 or 6 × 2, both moving 12 squares. Through repeated gameplay where students choose this interpretation themselves and verify equality through board movement, they internalize that the order of factors doesn't change the product. This property emerges from experience rather than memorized rule.

Working with factors between 1 and 6 keeps calculations within manageable ranges while covering most single-digit multiplication facts. Students practice facts like 3 × 4, 5 × 6, and 2 × 4 in contexts where quick calculation provides competitive advantage. The structure motivates accuracy and efficiency without isolated drill—students want to calculate correctly to move strategically.

The 156-space board creates opportunities for students to work with larger products as they progress. Early spaces involve smaller movements (1 × 2, 2 × 3), but as students advance toward the trophy, they work with products like 5 × 6 = 30 or 4 × 6 = 24. This progression supports development from emerging fluency toward more automatic recall as gameplay continues.

The position-swapping mechanic introduces inverse thinking: "I need to move 17 squares—what multiplication facts yield 17?"

Blue star squares requiring position swaps introduce strategic calculation with specific targets. If an opponent is ahead, students might aim to land on a star square, requiring them to calculate which dice interpretation will result in landing exactly on that space. This inverse problem-solving—working backward from a desired product to identify possible factors—develops flexible thinking with multiplication relationships.