Most upper elementary students can multiply reasonably well and understand place value in isolation, but connecting these ideas takes deliberate practice. Tenbeard's Treasure creates that practice by having students multiply constantly—then immediately deal with the place value consequences of their products.

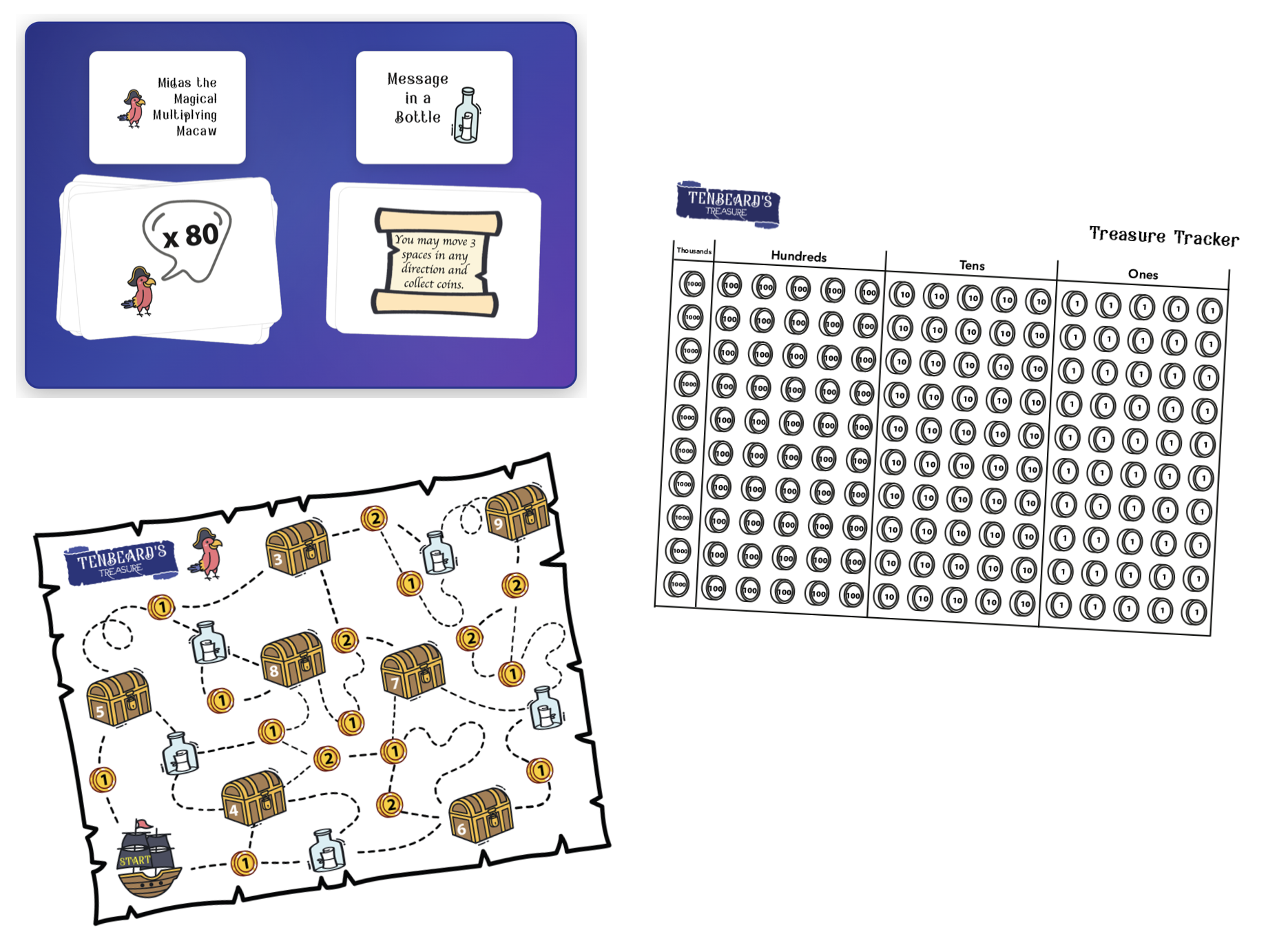

Here's how it works. Students move around a board collecting coins (values like 1, 2, 4, 7, 9). When they land on a coin or treasure chest, they draw a Macaw card showing a multiplier. Land on a 7-coin space and draw ×40? That's 280 coins to add to your treasure tracker.

The treasure tracker is where the place value work happens. It's a large grid with four columns—thousands, hundreds, tens, ones—each containing 10 rows of 10 circles. Students shade circles to track their treasure. Recording 280 coins means shading 2 hundreds, 8 tens, and 0 ones.

Each column holds exactly 10 rows—forcing students to regroup when they accumulate ten in any position.

This constraint forces regrouping. If you have 12 ones, you must swap 10 of them for 1 ten. The physical act of crossing out 10 circles in the ones column and shading 1 circle in the tens column makes the exchange concrete. Ten ones literally become one ten. Students who've been mechanically "carrying the one" in addition algorithms suddenly see why that works—the digit moves because 10 units in one place equals 1 unit in the next place.

When students draw a ×10 card, they see the digit shift happen. Four coins become forty coins, which means shading in the tens column instead of the ones column. The physical recording makes visible what's often taught as an abstract rule: "just add a zero."

Multiplying by multiples of 10 (like ×30 or ×70) requires decomposing the multiplier. To find 8 × 30, students typically calculate 8 × 3 = 24, then multiply by 10 to get 240. The tracker confirms this: 24 tens is the same as 2 hundreds and 4 tens. The representation flexibility—seeing 240 as "24 tens" or "2 hundreds and 4 tens"—is mathematically important and often glossed over in traditional instruction.

Competition adds useful pressure. Students want to calculate quickly and accurately because errors cost treasure. This motivates efficiency. Early in the game, students might shade 30 individual ones; later, they recognize they can shade 3 tens immediately. This shift from counting to place value reasoning is the pedagogical goal.

The game ends unpredictably—when someone draws the Tenbeard card from the deck. This variability means students work with different magnitudes. Some games yield totals in the hundreds; others reach several thousand. The final score calculation requires reading the entire place value notation: 3 thousands + 2 hundreds + 4 tens + 6 ones = 3,246 coins.

Message in a Bottle cards occasionally disrupt the multiplication pattern by offering bonuses ("collect 30 extra coins") or extra moves. These cards require students to shift between multiplication and addition, maintaining accuracy across different operations.