Factor Fiction builds fluency with factors and divisibility through strategic elimination. Students repeatedly identify all factor pairs of given numbers, then apply divisibility reasoning to narrow down suspects. The mystery context transforms what could be rote factor identification into purposeful mathematical detective work.

Each room in the hockey arena presents a factor riddle: students must find every factor pair of a mystery number. A factor pair consists of two numbers that multiply together to produce the target number. For 24, the complete set of factor pairs is 1×24, 2×12, 3×8, and 4×6. Finding all pairs requires systematic thinking—students develop strategies for ensuring they haven't missed any factors.

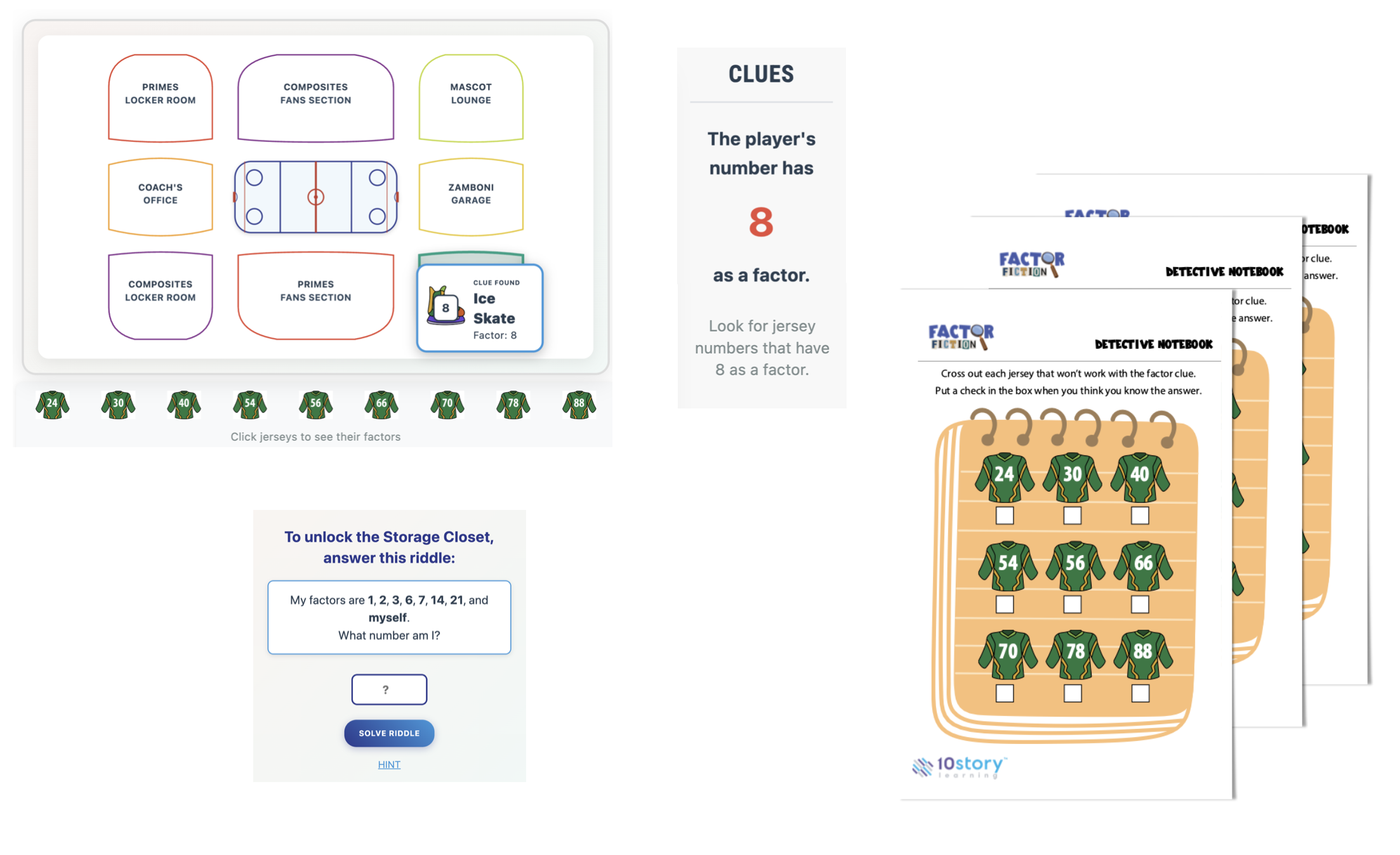

After solving each riddle, students receive a clue identifying a specific factor. They compare this factor against the jersey numbers of all remaining suspects. If the clue states "the thief's number is divisible by 7," students eliminate every player whose jersey number is not a multiple of 7. This process converts factor knowledge into logical deduction.

The elimination mechanic requires understanding divisibility from both directions. When checking if 56 should be eliminated given factor 7, students must recognize that 56 is 7×8—meaning 7 is indeed a factor of 56, so this suspect remains. But 54 cannot be divided evenly by 7, so that suspect is eliminated. This bidirectional thinking—from factors to multiples and back—strengthens number sense.

Jersey numbers 24, 30, 40, 54, 56, 66, 70, 78, and 88 create overlapping factor relationships that require students to collect multiple clues before identifying the culprit. Single clues rarely eliminate all but one suspect.

Finding factors systematically develops as students play repeatedly. Early attempts often involve random guessing—trying multiplication facts until something works. More experienced players develop organized approaches: testing small factors first (2, 3, 5), recognizing that factors come in pairs (finding 4 means 15 must also be a factor of 60), and stopping once they reach a factor pair that repeats (6×6 for 36).

The game exposes students to numbers that challenge common divisibility rules. While rules for 2, 5, and 10 are straightforward (even numbers, ends in 5 or 0), factors like 3, 6, 7, 8, and 9 require either memorization or calculation. Students who have internalized multiplication facts to 12×12 can identify factors quickly. Those still developing fluency practice multiplication relationships in a meaningful context.

Strategic thinking emerges from the elimination process. Clues revealing prime number factors (like 7 or 11) eliminate more suspects than clues about common factors (like 2). Students begin recognizing which clues provide maximum information—if only two suspects remain and both are even, a clue about factor 2 provides no new information. This metacognitive awareness connects mathematical properties to strategic decision-making.

The distinction between factors and multiples becomes operationally clear through gameplay. When students find factor pairs of the riddle number, they're identifying factors. When they check whether jersey numbers are divisible by the clue, they're testing if those numbers are multiples of the clue. This repeated practice with both concepts in complementary contexts builds understanding of their reciprocal relationship.